Eric Trump expressed a sense of triumph after Florida officials recently approved the donation of a valuable piece of Miami real estate for his father’s presidential library. “I got the library approved yesterday,” Trump stated on a podcast, adding that “we just got the greatest site in Florida and I’m going to be building that.” On another program, he mentioned taking the host’s suggestion to create a “fake news wing” — funded by money from lawsuit settlements with ABC, CBS, and other sources. This wing would showcase clips from “60 Minutes” and other programs that he claimed were evidence of media organizations’ animus against his father.

These statements by the president’s son offer a glimpse into the fervor of President Donald Trump and his family to construct a high-rise likely containing a museum that they claim will be unlike any other presidential library — and which could tell the story of his presidency only as he wants it to be told.

Much about the process remains shrouded in secrecy, with no federal rules requiring disclosure of donors — some of whom may have interests affected by White House policy — who are expected to contribute hundreds of millions of dollars. A recent filing, for example, states that the Donald J. Trump Library Foundation raised $50 million this year but does not provide donor names. It mentions $6 million spent for “program services” but lacks specifics.

The White House referred questions to the foundation, which did not respond to an emailed list of queries and has not indicated whether Trump might use part of the site for a hotel or other development.

It is also unclear whether the Trump library will function as its name suggests — providing a center for research of presidential papers — or whether museum exhibits would be reviewed by government historians. Trump might follow the example of former president Barack Obama, who created a private foundation that is building his Chicago center where the museum exhibits will not be subject to government review.

Running a center under the Obama model would require significant sums of money, which might explain why Trump’s strategy of using money from lawsuits against media companies and other sources has become essential.

Trump has not yet stated whether he will follow Obama’s example, but if he does, experts suggest he would be free to present his own version of his presidencies — including his false assertion that the 2020 election was stolen. That would contrast, for example, with the library of former president Richard M. Nixon, where the National Archives created an exhibit on Watergate that was vetted by nonpartisan government historians but criticized by some Nixon supporters.

Tim Naftali, who helped create that Watergate exhibit in his former role as the National Archives-appointed director of the Nixon library, expressed concern that Trump could create a museum that tells a misleading story about his presidency without oversight.

“If they are going to have a ‘fake news wing,’ it would be awfully hard for nonpartisan library professionals at the National Archives to swallow,” said Naftali, now a senior research fellow at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs.

But if Trump follows the Obama model, the National Archives would be powerless to object, he said. The archives would still control the presidential papers, which belong to the federal government and would gradually be made available online after undergoing review for classified material.

That model will become clearer once the Obama Presidential Center, as it is called, opens in June. Asked how Obama’s center will tell his story, a spokesperson said in a statement that Obama and his foundation consulted with leading independent historians and “take the study of history and the U.S. Constitution seriously, and these values are reflected in the work at the center — and in particular, the Museum.”

But Curt Smith, a former speechwriter for President George H.W. Bush who wrote a book on presidential libraries, said in an interview that the Obama model “is a terrible example to follow” because it allows a former president to write whatever script they choose. “I would be truly alarmed if the Trump library followed that model,” he said.

There is no law requiring the construction of a presidential library; with or without it, presidential papers and artifacts are the property of the federal government and controlled by the National Archives. Indeed, after Trump’s first term, he did not establish such a center. When Trump took some classified presidential papers to Mar-a-Largo in Palm Beach, Florida, he was charged with willful retention of national defense secrets. The case was dismissed.

From the earliest days of his second administration, however, Trump has focused on raising millions of dollars for his center, while Eric Trump focused on gaining land for the project. Once President Trump decided to build his center, he had no choice other than to raise private funds because Congress does not provide taxpayer money for construction.

The rules say not only that the construction funds be privately raised, but also that an additional 60 percent of that cost be provided as an endowment if the government maintains the facility. That requirement was enacted because the National Archives is spending $91 million annually to cover expenses of most earlier presidential libraries, almost one-fourth of its congressional budget. As a result, the Archives has been negotiating deals that would transfer much of that cost to foundations.

“Today, preserving the presidential library system requires acknowledging these facts and addressing mounting expenditures across the system,” Jim Byron, senior adviser to the archivist of the National Archives, said in a statement to The Washington Post.

If Trump keeps his center private, as is widely expected, his foundation would be responsible for maintenance and would not cede control of the museum to the National Archives — saving taxpayer money while enabling him to write his own story.

That has led to the current situation in which Trump is raising funds from the settlement of lawsuits against the media and other sources.

‘We gave away very valuable land’

On Sept. 16, a vague ad appeared in the Miami Herald announcing that Miami Dade College would hold a public hearing to “discuss potential real estate transactions.” There was no indication that a 2.6-acre property in downtown Miami — which is appraised at about $60 million but which real estate brokers have said could be worth $300 million or more — was about to be donated to Trump’s library foundation.

Seven days later, at 8 a.m. Sept. 23, the meeting of the college board of trustees convened. Chairman Michael Bileca called for approval of Agenda Item A, a proposal to convey an unnamed piece of property to an entity known as the “Internal Trust Fund of the State of Florida.” Again, there was no mention of land being given for a Trump library. Bileca opened the floor for discussion; there was none. The motion was passed unanimously by the seven members. Bileca did not respond to a request for comment.

At exactly 8:03 a.m., according to board minutes, the meeting adjourned and the deal was done.

Gov. Ron DeSantis and his cabinet then announced they had agreed to give the land to the Trump library foundation. The only requirement is that construction begins within five years and that it “contains components of a Presidential library, museum, and/or center.”

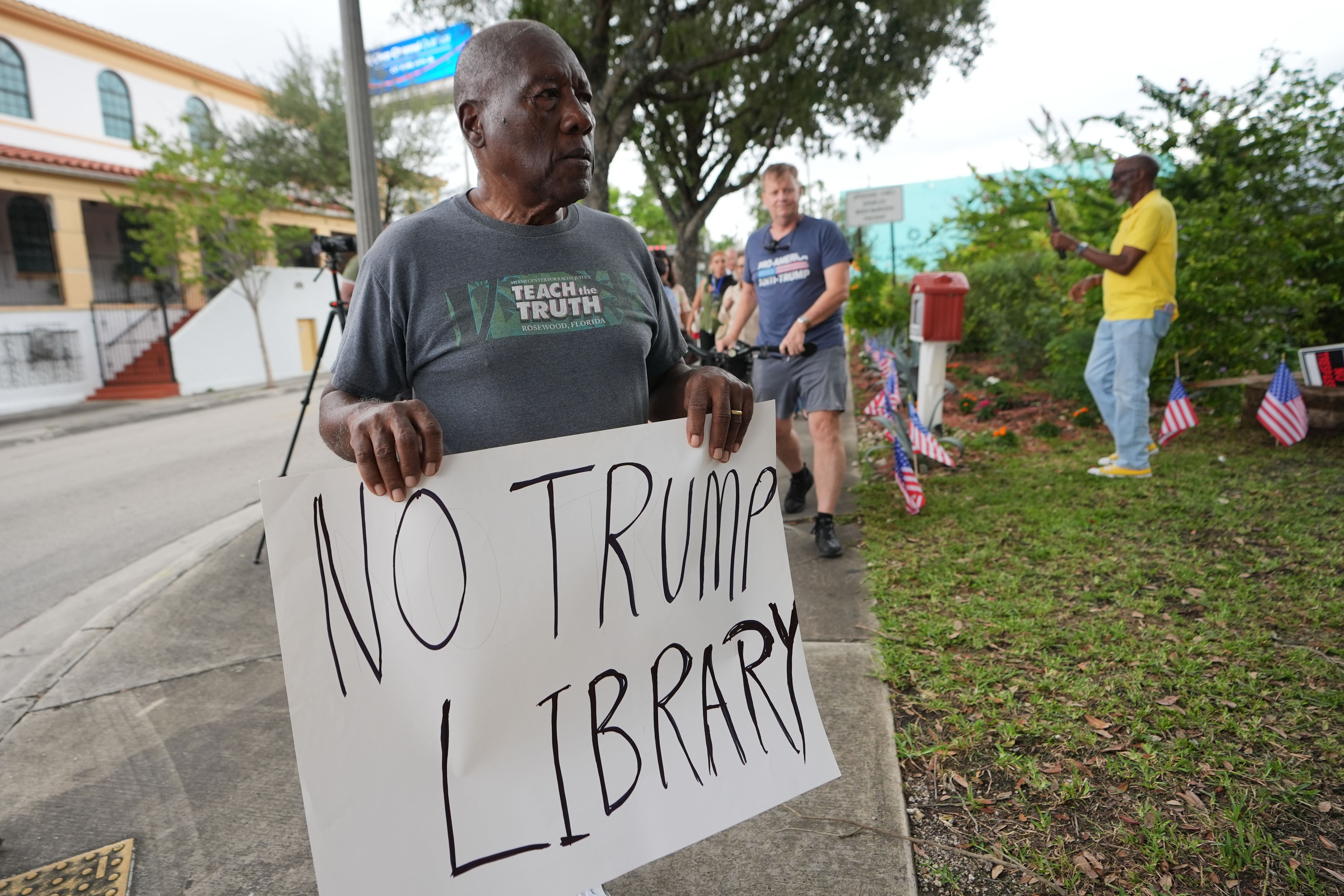

The secretive deal took many people by surprise — including at least some members of the college board of trustees — and caused an uproar among critics.

Roberto Alonso, vice chair of the Miami Dade College board of trustees, said the governor’s office sent a letter to the college asking for the land transfer to the state, without explaining why.

“When I found out that this was exactly what the state wanted was literally right after we voted,” Alonso said.

Alonso said because Miami Dade is a state college, the land is owned by the state, so his board had little choice but to do what DeSantis wanted and convey the deed.

He called the library an “incredible opportunity for our students and our community.” The college did not respond to a request for comment.

The property is a parking lot on the downtown campus of the college. It’s next to the Freedom Tower, an iconic and recently restored landmark on Biscayne Boulevard often referred to as the “Ellis Island of the South.”

The plan drew immediate backlash from many in the Cuban community who said Trump’s immigration policies contrast with the treatment their families received under previous administrations.

The college board’s approval also became the target of a lawsuit filed by Miami historian Marvin Dunn, who said the vague notice about the action violated state government Sunshine Laws. The judge in the case set a trial date for next year, but the trustees held a second vote Dec. 2, this time with input from the public, that ended in the same result — a unanimous vote.

Dunn’s lawyer, Richard E. Brodsky, said in an interview the lawsuit has succeeded in gaining a temporary injunction that prevents the conveyance of the land pending a further order of the court.

“It’s not over yet,” Brodsky said.

Miami mayor-elect Eileen Higgins — the first Democrat to win the office in almost 30 years — said before Tuesday’s election that she had questions about the deal.

“We gave away very valuable land to a billionaire for free. That doesn’t make sense to me,” she said during a televised debate this month.

Dunn said Eric Trump’s statement that the library will be an “iconic building” raises the alarming prospect of “a 47-story condominium hotel banquet hall” or other oversize structure.

“If the argument is that this library is going to bring tourism and economic development to the wider region, that may well be true,” Dunn said in an interview. “Then why doesn’t the foundation pay for the land? Why give that to them for free?”

DeSantis said in September that “we had worked and negotiated” other possible locations for the library, including at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton, which is in Palm Beach County about 30 miles from Mar-a-Lago.

“But their preference was for this land, next to the Freedom Tower. So you’re going to have a presidential library in the state of Florida, which I think is good for the state of Florida. I think it’s good for the city of Miami,” he said.

‘A possible tool for corruption and bribery’

While the state filing by Trump’s library foundation doesn’t disclose funding sources, President Trump has spoken often about some of them. The largest projected donation is a gift of a Boeing 747-8 aircraft valued at $400 million from the Qatari royal family — which has many interests in Washington policy — that would replace Air Force One and then be given to his library. It is not clear how or whether the plane could be exhibited at the Trump library as Ronald Reagan’s Air Force One is exhibited at his library in California.

Other funds for the library stem from payments from media companies — some of which have interests before the government — to settle lawsuits filed against them by Trump. These include: $22 million from Meta Platforms, Facebook’s parent company, part of a settlement to resolve a lawsuit over the company’s suspension of Trump from the platform in the wake of the events of Jan. 6; $16 million from CBS; $15 million from ABC; and an unspecified part of a $10 million settlement with X, formerly known as Twitter, which had banned him from the platform. In addition, millions of dollars raised from private interests left from Trump’s inauguration may be transferred to the library foundation.

These gifts and payments, and the potential of hundreds of millions more from unknown donors, have led Democrats to introduce the Presidential Library Anti-Corruption Act, which would ban fundraising until after a president leaves office, except from nonprofits. It would require a two-year delay after a president leaves before donations can be accepted from foreign nationals or foreign government, lobbyists, individuals seeking pardons and federal contractors.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Massachusetts) issued a report in support of the legislation that said Trump “may be using his future presidential library as a possible tool for corruption and bribery while still in office.” The report then listed donations intended for Trump’s library. Warren was unavailable for an interview, an aide said.

Presidential libraries are seen as a crucial pillar for portraying the history of White House occupants and making their materials widely available. They have proven invaluable to historians and others seeking to piece together the strands of a presidency that often become clearer in hindsight; author Robert Caro used materials at Lyndon B. Johnson’s presidential library in Texas for his prizewinning multivolume biography.

But in recent years, historians have raised concerns that presidential libraries have focused more on hagiography than clear-eyed biography — particularly as increasingly large sums have come from private donors, including those who have interests before the federal government and who favor a particular storyline about a president.